The alternative guide to transferrable skills

001

I became interested in sound design for film while studying Music technology at uni, and my dissertation proposed a theory about how sound effects in a film can subconsciously evoke emotions in the viewer.

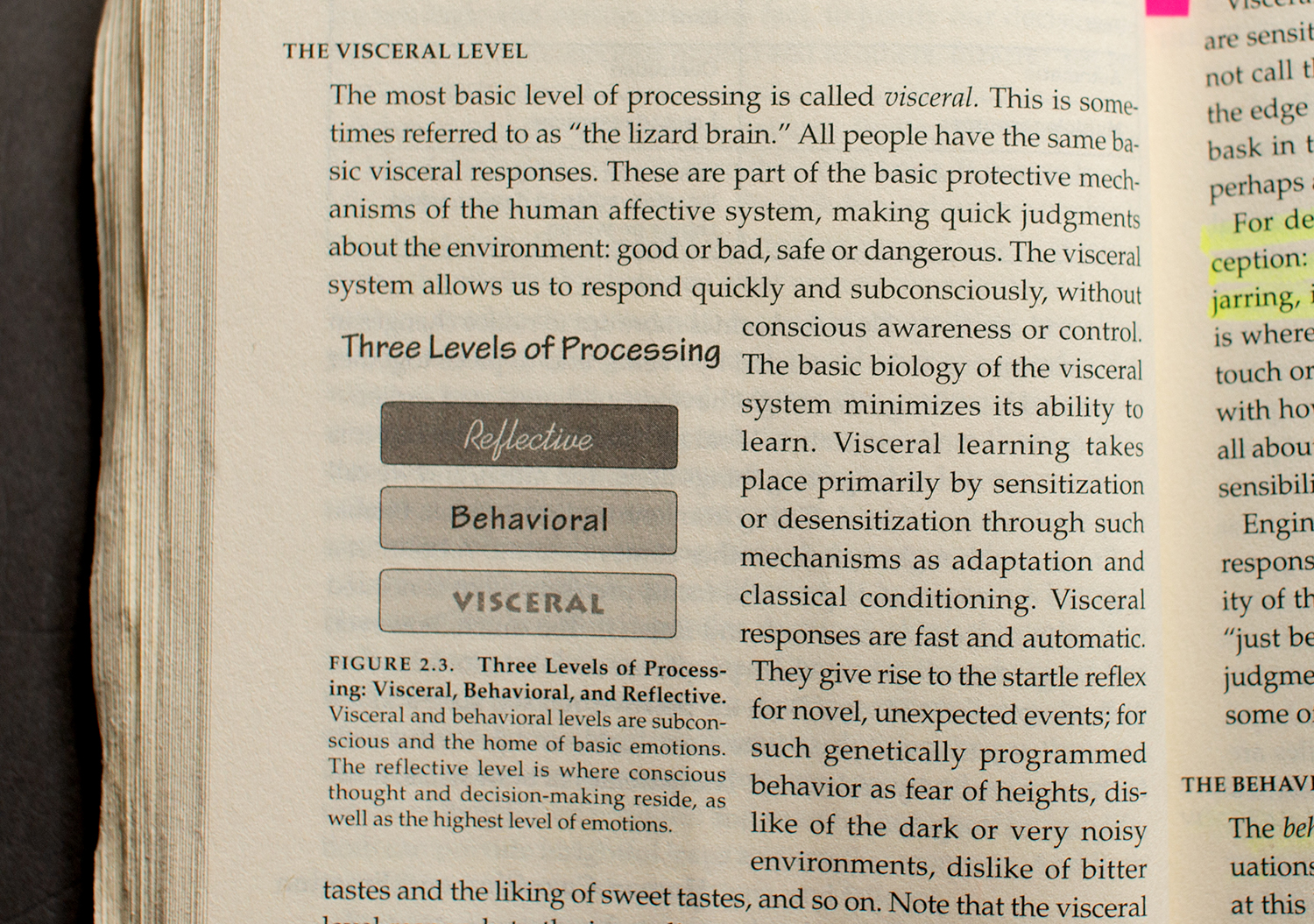

Although it is a type of design, I had not considered the connection of film sound with user-centred design until recently when I read Don Norman’s chapter on the human emotion system, and the implications it has for designers.

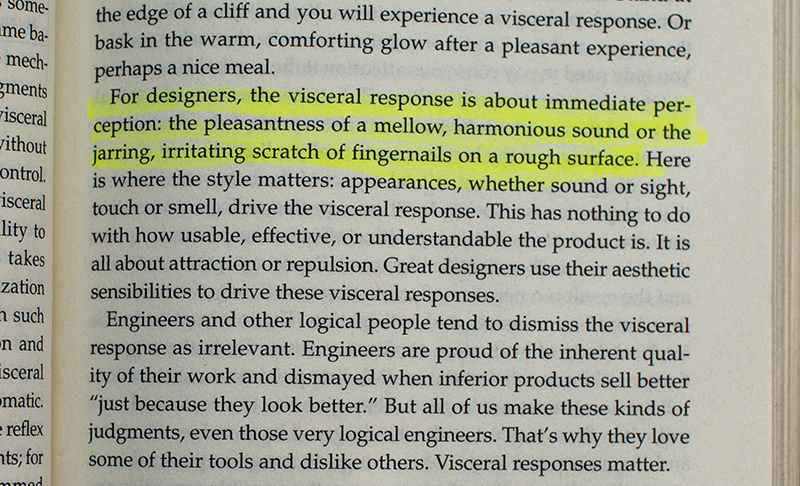

The visceral level he describes is based on the same understanding of neurology that underpinned my theory of sound design and emotion.

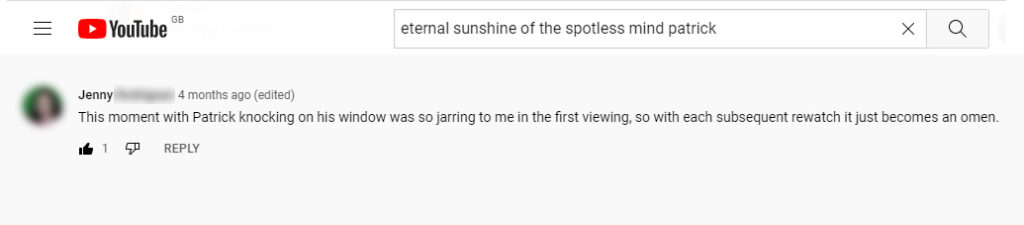

My dissertation focused specifically on the sound effects rather than the music, and this scene from Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is a perfect example of the psychological effect I attempted to explain.

Listen in from about 50 seconds and you can hear a shrill alarm. There is no object on the screen which makes this sound, and the viewer is not intended to notice. They are focused on watching the characters and following the dialogue.

The alarm gives a background tension to the scene for the introduction of Patrick. He is the films antagonist, and the sound is used deliberately to tell the story, associating his character with threat.

Combined with the horror-esque close-up on Joel in the car, and the sudden interruption of the knocking on the window, the sound effect introduces Patrick with unease, and supports Jim Carey’s wary expression to create an unsettling sequence.

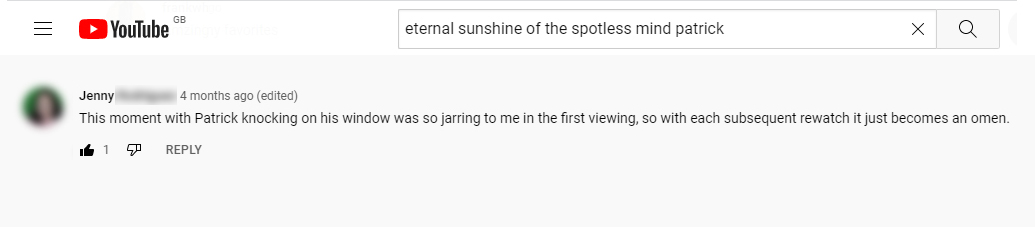

This lady in the youtube comments describes it perfectly…

She may not have noticed the alarm sound the first time she watched the film because viewers don’t normally focus on sound effects, but it plays a key part in making that moment so jarring to watch. It was included in the soundtrack deliberately as a story telling device.

My dissertation proposed a theory of how and why sound effects can be used in this way. The original essay is a long, long read, and makes Don Norman’s classic seem like a breeze.

Hopefully I’ve improved my UX writing skills since then, so I’ve summarised the main points here. It’s still pretty interesting, and gladly not the load of old rubbish it could have been.

Its based around three key aspects of psychology and neurology:

- Focused attention

- The role of the amygdala in emotional responses

- The memory system and emotional association

1. Focused attention

The best way to explain focused attention is with a phenomenon known as the ‘Cocktail effect’.

The cocktail party effect is the phenomenon of the brain’s ability to focus one’s auditory attention on a particular stimulus while filtering out a range of other stimuli, such as when a partygoer can focus on a single conversation in a noisy room.[1][2] Listeners have the ability to both segregate different stimuli into different streams, and subsequently decide which streams are most pertinent to them.

Wikipedia

Basically, its your ability to tune out sounds that are of no importance, and focus on sounds that are.

For example, if you were at a cocktail party in a conversation with a boring person who was moaning on about Covid or Brexit, and you overheard something of more interest, you can easily tune out of the less important conversation.

It’s easy to shift the focus of your attention away from the brexit bore onto the person buying the drinks, to the point where technically your ears still pick up what they are saying about non-tariff barriers, but you don’t actually hear it consciously.

The relevance of this to film sound, is that the sensory data is still processed, even if you don’t hear it. Although you are consciously focused on something else, your brain will still receive the sensory signals of the sounds you’re not listening to.

2. The role of the amygdala in emotional responses

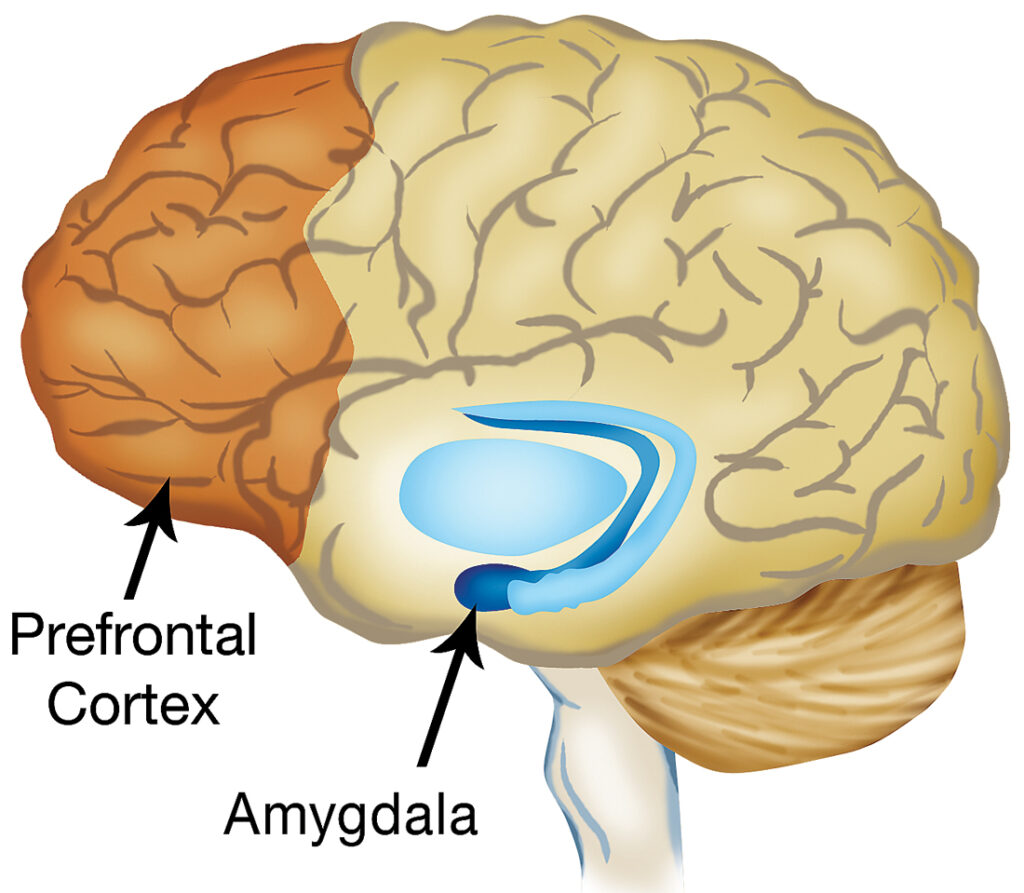

The second aspect of the study is the role of the amygdala, specifically how fast sensory information reaches this important part of the brain.

The amygdala is part of the limbic system, and is known to regulate emotional responses to sensory information.

The limbic system is the part of the brain involved in our behavioural and emotional responses, especially when it comes to behaviours we need for survival: feeding, reproduction and caring for our young, and fight or flight responses.

More trustworthy source here

For example, if you hear the sound of snapping twigs behind you in a dark forest, the sensory information will travel from your ear drums to the Amygdala, which will then elicit the emotion of fear. This will most likely trigger the fight or flight reaction, and all the physical effects that come with fear, such as increased heat rate, dilated pupils, and the subjective feeling of ‘fear’.

My dissertation cited research that showed through experiments on rats, that the sensory information travels from the ear to both the Amygdala and the Pre-frontal cortex, which is responsible for conscious thought.

Importantly, the experiments showed that the sensory signals arrive at the Amygdala before arriving at the Pre-frontal cortex, and elicit an emotional response before you have even consciously processed the information.

So you may experience the fight or flight response before you have even consciously heard and processed the sound.

There are plenty of examples of this if you think about it long enough, but the example from the cited research was if perhaps you were walking through a wood, and you saw an object that looked like a coiled up snake. The Amygdala may automatically trigger the fight or flight response and the fear emotion, but the same sensory signals will then reach the Cortex, and as you consciously process these signals, you realise it is actually a just coiled up hose pipe that poses no danger.

My dissertation proposed that the automatic emotional reaction caused by the fast response of the amygdala, combined with the effect of focused attention, explains how sound effects can subconsciously add emotional colour to scenes in a film.

While you may be paying attention to the dialogue or expressions of the actors on screen, your brain is still receiving the sensory information of the background sound effects, even though you don’t consciously hear them. You are focused on the free Margarita and not listening to the Brexit bore, but the implications of the Northern Ireland protocol are still going in.

Because this sensory information is still reaching the amygdala, theoretically it is still able to elicit an emotional response, even if you don’t hear it. And this is why the alarm sound in the clip from Eternal Sunshine can still add tension to the scene, even though you aren’t paying attention to it and don’t consciously notice it.

3. Memory and emotional association

And the last piece of the puzzle lies with the Hippocampus. Why do certain sounds and sensory information elicit an emotional response? By association and memory.

The Hippocampus connects the different sensory elements of a memory, and the Amygdala creates an emotional bond between these elements. For example in a car crash, you may hear the sound of screeching brakes, feel the sensation of flying sideways, smell the burning rubber of the tyres on the road, and see the oncoming car heading towards you.

Together the Amygdala and Hippocampus attach an emotional core to the memory, connecting these different sensory elements and associating them with the fear you experienced.

So the next time you hear screeching brakes, or smell burning tyres on a road, this in turn will recall the other elements of the memory, including the fear response. So the sound of screeching brakes could forever evoke the feeling of fear.

In the film clip from Eternal Sunshine, the sound effect used to create unease and tension is a shrill alarm. Needless to say we all associate alarm sounds with danger – that is the very purpose of an alarm. Its a warning, and it puts us on our guard. Perfect for introducing the antagonist in a story, even though the viewer will not notice the sound.

Developing association

I went further to propose how emotional association with sounds could be built up through the duration of a film. I suggested that by using a distinct sound effect at key emotional moments in the story, you could subconsciously condition the viewer to associate the sound with a particular emotion.

The sound could then be used later in the film to recall that same emotion. In theory you could program the film viewers brain like Pavlov programmed his dogs to expect food when he rang a bell.

In film score terms, this is called a Leitmotif:

A leitmotif in film music is a succession of notes, harmonic progressions, or rhythmic patterns associated with a particular character, setting, or theme.

Masterclass

Classic leitmotif examples include ‘The Imperial March’ from Star Wars, and the stabbing violins in the shower scene from Psycho.

The effect of leitmotif’s are summed up nicely in another handy youtube comment…

The Amygdala and Hippocampus probably have something to do with those goosebumps, and if we look back at the first youtube comment, the lady seems to be describing a similar thing: ‘with each subsequent rewatch it just becomes an omen‘.

You wouldn’t normally expect to see youtube comments as references in an academic study, but these people are the users!

I devised an experiment to test the ideas in the study by using different versions of sound effects in the same clip, and asking people to rate how they felt when watching. I’m not sure how reliable the results were as its quite hard to measure, especially with very short clips, no context of a story, and sitting in your housemates room having beers. But maybe its the kind of thing you could observe in a usability session?

UX design

Another cliche used in film sound is a crying baby. The human brain is hard wired to experience stress when hearing the sound of a crying baby – for obvious evolutionary reasons – so parents do not neglect their children.

The neurological processes described above explains exactly why the sound of a crying baby is so effective at adding tension and stress to a scene in a film – even quietly as a background sound effect.

You may not notice the sound of a baby crying quietly in the background because you are paying attention to the characters and dialogue, but you will still experience the emotional tension triggered by the sound.

It produces the same visceral response described by Don Norman in The Design of Everyday Things. Although I would hazard a guess that most UX designers strongly aim to avoid inducing high levels of stress and fear in the user.

But it isn’t all just about fear, stress and anxiety. Don Norman also relates the visceral level to aesthetics:

I think this explains exactly why great photography works so well on the landing page of an airline website: It creates a positive visceral response, subconsciously evoking positive emotions and associating the task in hand with the users ultimate goal, while they are focused on finding the best flights for their trip.

And this probably explains why most airline websites use striking, evocative images on the landing page. The designers may not have considered the neurology in so much depth when choosing their hero banner images, they probably just intuitively picked an image that works well – but maybe that backs up one of the main points – it all happens subconsciously.

As Don Norman says on the page above: ‘Great designers use their aesthetic sensibilities to drive these visceral responses’.

Or maybe they have just been reading youtube comments?

For a more credible source than youtube comments or junior UX designers, this page neatly explains the scientific understanding of the brain systems described in this blog.